Introduction

I am currently working on listing the University of Leicester’s administrative archive, as part of the National Lottery Heritage Fund supported “So That They May Have Life” project, celebrating the University’s Centenary. The papers that I have been looking at cover the first thirty or so years of the University’s life, covering the founding, the development of various courses and departments, fundraising and much of the day-to-day minutiae that goes into the creating and running of a University.

There are a range of interesting stories that have come to light as a result of this blog post: my previous post examined the role of advertising in those early years, and my third and final post will examine some of my favourite discoveries in the archive. In today’s blog, I wanted to explore one area that I found repeatedly cropping up as I worked through the collection – the impact that the Second World War had on what was at that time University College, Leicester.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for such a large and all-consuming event, the impact of the war reverberated through all aspects of college life. I have tried to pick out here some of the key impacts it had – surrounding preparations for bombing, evacuations and postings, supplies and international friendships.

Preparing for Bombing

Whilst Leicester itself suffered some bombing during the War, the University College was spared. Despite this good fortune, preparations for potential bombing needed to be put in place, to try and keep those who lived and worked in the University College safe if the worst were to happen.

This involved practical changes to the structure of the buildings; developing safe locations that could be used as air raid shelters, often requiring the reinforcing of walls (ULA/ADM/4/1/ARP). The archive contained a sample of black-out material, as black-out curtains were created and fitted, and heating was introduced to the basement underneath the Domestic Science Hostel so that it could serve as a refuge (ULA/AD/H2/4/5). The equipment records of the University College record the fitting of Air Raid Bells (ULA/ADM/4/1/ESEQ/6), and provisioning of shelters.

Lists of fire watchers were drawn up (ULA/ADM/4/2/FWS) consisting of staff and student volunteers. Insufficient staff could be found to cover college holidays, and occasionally individuals were found to be absent from their posts. Despite this, when the call went out for volunteers to serve shifts at local primary schools (ULA/ADM/4/1/ARP), helping to evacuate were it to become necessary, many people signed up.

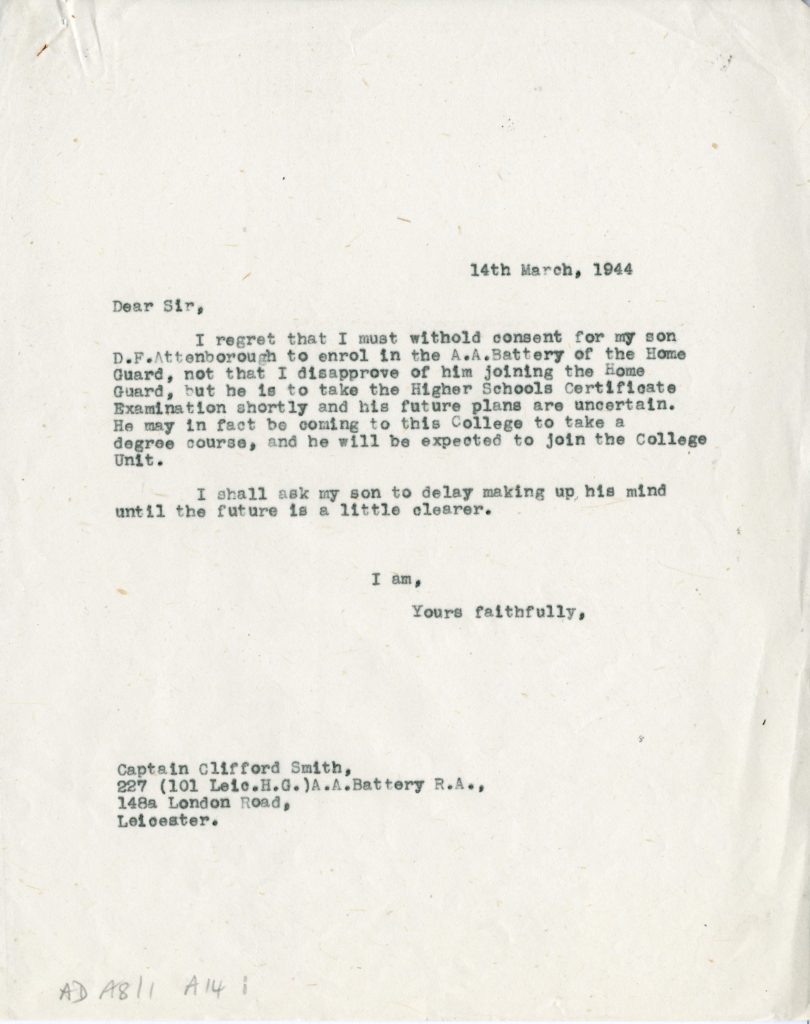

This eagerness to help can also be seen in correspondence from F.L. Attenborough (ULA/AD/A8/1A) – His son David wished to enlist in the A.A. Battery of the Home Guard. However, this request was refused by F.L. Attenborough, both because David needed to study for his exams, and because he would then go away to university. Despite all the preparations made, Leicester was itself much less badly affected than several other areas of the country.

Evacuations and Postings

Considered a relatively safe location, various groups found themselves evacuated to Leicester. Initial plans to relocate University College Hull (ULA/ADM/4/1/HULL/1940) were abandoned after a rapid flurry of cost estimates, but students from King’s College of Household and Social Science were evacuated to Leicester, sharing the University’s premises (ULA/ADM/4/1/KCHSS) for six years. (For more information on this please see this exhibition hosted by King’s College London). A number of refugee students also joined the college (ULA/ADM/4/1/R/REF), many with reduced fees or free places.

The University College played host during the war to the BBC (ULA/ADM/4/1/BBC), with an aerial mast being constructed in the college grounds, and rooms being rented. Furthermore, the Station Director of the BBC took advantage of the wealth of knowledge surrounding him, arranging for talks by members of college staff (ULA/ADM/4/1/BBCT). Between 1942 and 1944, the University was also the host of Commandant R. Foulquies, the local Free French Representative. Far from the University being emptied by the hostilities, it ended up with a wide range of people calling it home.

At the same time, courses were supplied for a range of soldiers from Canada and America (ULA/ADM/4/1/CAL, ULA/ADM/4/1/CDA), alongside for the British Auxiliary Territorial Service – the women’s branch of the Army (ULA/ADM/4/1/ATS). Generally such agreements seem to have gone well, although there was an issue with American soldiers regularly missing class as they had to “buy their cigarettes and candy from the U.S. Army’s travelling store every other Thursday”, a task which would often take the whole afternoon. Despite this, the courses appear to have been popular and well received.

Such was the demand for these courses, that often only limited numbers could be supplied. After the war, the college played host to returning accountants and others whose qualifications may have lapsed during the fighting (ULA/ADM/4/1/HVS/1936). This helped local businesses resume their operations following the de-enlistment of their workers.

Supplies

Throughout the war, and in the years immediately following it, many items were rationed. Ensuring a working fire pump required requesting fuel from the Ministry of Fuel and Power (ULA/ADM/4/1/FGP), and a similar request was needed to heat the greenhouse (ULA/ADM/4/1/GRE). Paper supplies were also limited, with advertisements in newspapers being reworked and unnecessary words removed in order to try and fit within strict size limits, and with only limited repeats (ULA/ADM/4/1/Adv/G/2).

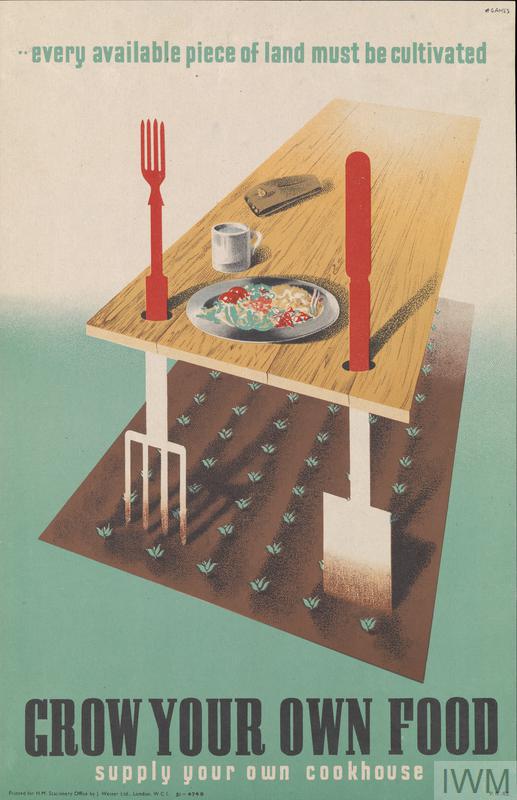

The supply of academic dress was also limited, as material for robes was in short supply (ULA/ADM/4/1/GOWN). Academic robes also initially needed clothing coupons – 8 for a standard robe, and 32 for a Doctor’s Robe and Hood. However, this was later relaxed, and therefore the only difficulty lay in ensuring a supply of the material. During this time, often orders were only partially fulfilled. Meanwhile University railings were removed for the war effort (ULA/ADM/4/1/R/RAI), leaving only those around the allotments in place. Much of the University’s green space was used to grow food (see poster below for Government encouragement to be self-sufficient). Damage to buildings could also cause problems in getting supplies, with some confusion over accounts held with Eyre & Spottiswoode publishers, as “the whole of (their) premises were destroyed by enemy action” (ULA/ADM/4/1/E) and so it was unclear which of their orders had been fulfilled.

International Friendships

Despite the constant threat of bombs, new arrivals and limited resources, the University and individuals within it formed strong friendships during the war. F.L. Attenborough’s private correspondence (ULA/AD/A8/1A) reveals both his support for the Polish Children Rescue Fund, and his concern for securing a ballet scholarship for Helga Bejach (one of two Jewish refugee sisters taken in by the family).

There was also clear friendship between Attenborough and Captain Dawes of the American Forces, thanking him “for the two volumes of songs you have sent me. At the moment I am not sure whether I ought to be grateful or not because from early morning until late at night I am hearing about “The Cowboy who wanted to be buried on the Prairie” or “Who Done ‘er Wrong”” (ULA/ADM/4/1/CDA). These gifts and connections between staff and their visitors show a sense of connection across countries. Both before and after the war, there were attempts to encourage students to spend time abroad – with discussion with Dr. Kurt Blohm of the Deutsh-Englischer Kreis regarding summer camps during1938, and a decade later the Foreign Office enquiring about the possibility of British Students spending a semester in Germany (ULA/ADM/4/1/GER). There was also a request to supply Chinese Universities with books in 1939 (ULA/ADM/4/1/CUAB), part of an ongoing Chinese-Anglo relationship. Over the following years, connections between the University of Leicester and other universities abroad have only strengthened.

Finding information in an archive can be challenging – it might be obvious that information about the war’s impact would be contained within topics such as War (ULA/ADM/4/1/WAR), or Air Raid Precautions (ULA/ADM/4/1/ARP), but it’s presence in topics such as Gowns, Caps & Badges (ULA/ADM/4/1/GOWN) or the BBC (ULA/ADM/4/1/BBC) may be less expected. The war had an impact on all aspects of University life, and evidence of this is threaded through files from the time. This chance to make discoveries and links is part of the true magic of archives, revealing stories from the past and showing an image of a university facing adversity driven by co-operation. Without these records, such stories might well be lost.

Jenni Hunt, temporary Archive Assistant, 25 March 2021.