Research volunteer Patrick Breen remembers his Leicester childhood and discusses his connection to the city and University.

My name is Patrick, (Patch) Breen. When I was a kid playing on the street (as you did in the Fifties) I wore glasses because I had ‘a lazy eye;’ it could have been the result of measles which I suffered from when I was six years old, along with whooping cough and pneumonia, in quick succession. Because of the ‘lazy eye’ I had to wear a patch over the ‘good’ eye- as a potential cure for the condition, and the kids on the street, the ones who didn’t know me, just kept calling me, ‘that kid with the patch on his glasses,’ and later just Patch instead of Patrick. The name stuck.

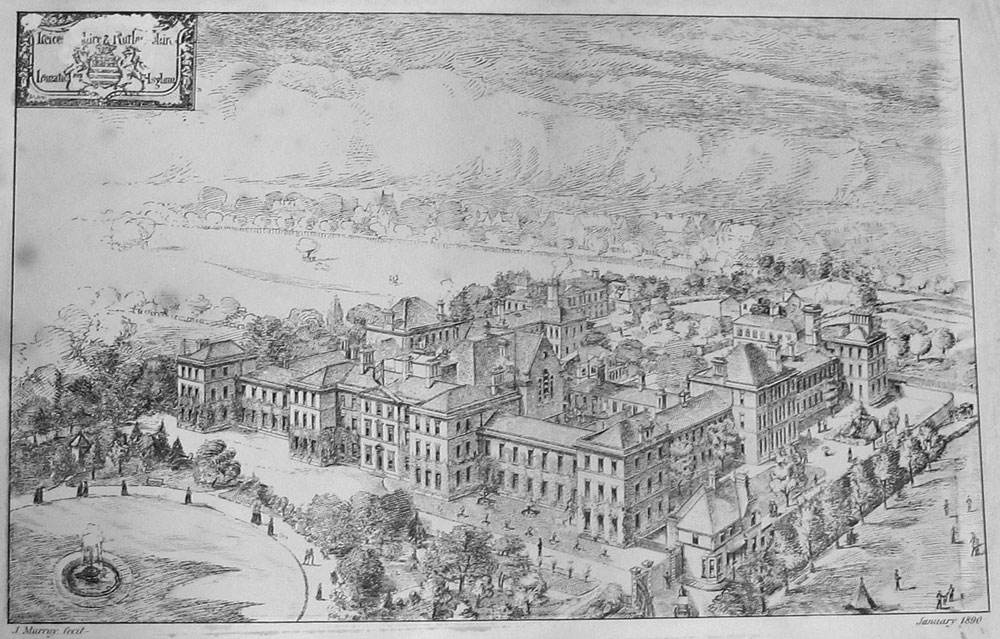

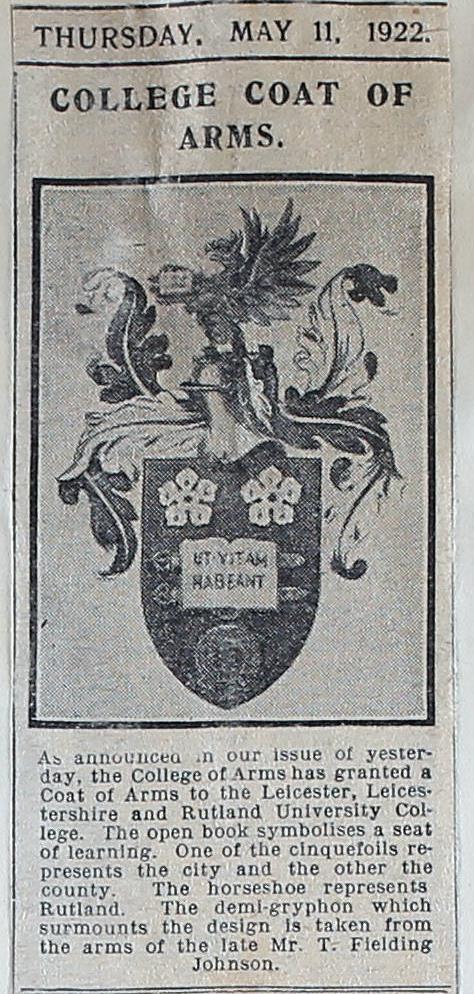

I attended two faith schools: Sacred Heart Primary and Corpus Christi Secondary and left at fifteen with no exams taken. I later did a degree in Sociology at Leicester (as a mature student in my late thirties) from 1989 to 1992 and ended up working for Mori Poll as a researcher. My son Damian also did his bachelor and masters degrees at Leicester and went on to Warwick to do is PhD; he’s now in the Criminology department at Birmingham City University. Leicester University is kind of in the family, I guess. I know little about the early history of the University, apart from the fact that the original building, Fielding Johnson was previously the Leicestershire and Rutland County Asylum, then a hospital to treat medical casualties, during the First World War, becoming The Leicestershire and Rutland University College in 1921. I’d like to find out what the music scene was like in the early years of Leicester University, were there gigs, students dancing to local bands playing covers like Fats Wallers “Ain’t Misbehavin,” a big hit at the time, or no music scene at all- which leads me on to the fact that I’m also an amateur musician myself, playing guitar, bass, steel pan and even singing. Now retired, I have two grandchildren and Leicester U3A to keep me busy.

Although from Irish Heritage, I’m born and bred in Leicester, and love the city, particularly the town centre: the cafe’s, and bars and feeling of vitality in and around these places. There’s a cafe on Granby Street that I often go to or walk into town and just sit and watch the buskers, playing every kind of music you can imagine from Jazz to Gospel. I love early August and Carnival, which really seems to bring the town alive. I’ve played Carnival many times with Steel Revolution, a band I have been a member of for over forty years. In fact, I remember playing on the first Carnival parade, originally created by Elvi Morton and Walton George.

You really know a tune when you’ve been playing it on the back of a lorry for three hours and had a little light refreshment to help you on the journey. Music helps me along my journey of life too. When the nights draw in, I often walk along the Golden Mile and look at the Diwali lights that turn into Christmas lights in December. Fantastic colours, fantastic feeling, with the tall Wolsey Flats- where my parents first met in the Forties, when the original building was a hosiery factory- looking down on the whole atmospheric scene.

I first volunteered in the 1980’s for Wesley Hall in Highfields, a Methodist Community Project linked to Age Concern at the time. I used to collect an Age Concern van from town and then pick up elderly, members for a lunch club at Wesley Hall. After lunch we would go for a run out around Leicestershire and then I would drop everyone home and take the van back to Clarence House on Humberstone Gate.

I’ve now found myself back at Wesley Hall, but with the Mental Health Service there, singing and playing for members on Friday mornings and helping with the Art Session on Wednesday mornings. Members enjoy themselves at the centre, forget their troubles for a while, and I guess I do as well; there’s a sense of community, a sense of belonging in the centre- the outside world is on hold for a while, a good thing I’d say.