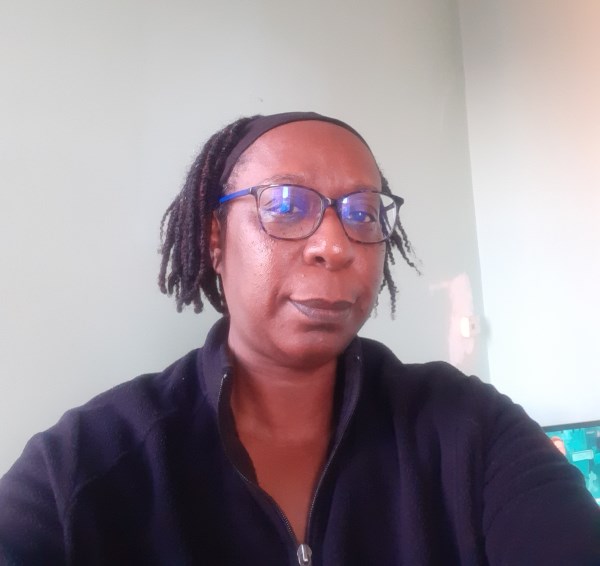

Our latest volunteer blog post introduces Jacqui Sealy, who will be researching women scientists at Leicester.

I am looking forward to volunteering on the “So that they might have Life” project. I am particularly drawn to researching the women in science strand. This will involve conducting research, to uncover the hidden history of women scientists, at the University of Leicester

I have always had an interest in science but had little opportunity to pursue it, until I became an adult.

I attended a girls only secondary modern school in the mid-70s, which would not employ a physics or chemistry teacher to teach at G.C.E., because it was decided that not enough of us were interested in learning those subjects. The only sciences offered were maths and human biology.

I went to a sixth form that was transforming from a boys only school to a mixed sixth form. I was told that I could not do Biology A level, because studying arts and science subjects together was not allowed. Obviously, this made no sense, but without encouragement, I did not have the confidence to challenge this decision and I ended up studying arts and social sciences, including at university.

I have always enjoyed many activities and interests in various arts but had a sense of missing out on science. As an adult, I successfully completed a G.C.S.E. Astronomy course at evening class and then did a couple of distance learning courses in Astronomy and Cosmology. I love the amazing, beautiful images of the solar system and the universe that we have from the telescopes in space. I find them to be awe-inspiring and they are there for anyone to see. Though I haven’t studied the subjects recently, I still enjoy the challenge of trying to understand the new theories and discoveries.

Two of my science heroes are:

Dr Maggie Aderin Pocock: British/Nigerian space scientist, science educator and co-presenter of BBC’s The Sky at Night programme. I had the pleasure of hearing her give an excellent talk at Loughborough University a few years ago, on the future of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). She reinforced my admiration of her as someone who challenges stereotypes of scientists, who has a passion for encouraging children’s interest in science and aims to make it more accessible to everyone.

Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell: She is a British astrophysicist and astronomer, who discovered pulsars, providing the first direct evidence for the existence of rapidly spinning neutron stars. Her supervisor was awarded the Nobel prize for it in 1974, but Jocelyn was not. She did not complain but went on to receive many other awards and recognition. I admire her because of the way she carried on building her career, despite the huge slight of not being jointly awarded the Nobel prize and being determined to help people who would not usually have access to physics. She has received many awards and accolades since then, including a £2.3m Breakthrough prize which is being used to fund people under-represented in physics. She said in 2018,

A lot of the pulsar story happened because I was a minority person and a PhD student. Increasing the diversity in physics could lead to all sorts of good things.

from an article by Ian Sample, in The Guardian on 06/09/2018

I have lots of interests, so volunteering with this project is a good opportunity to focus on one of them. I think that it may help me to decide what I want to do in the future.