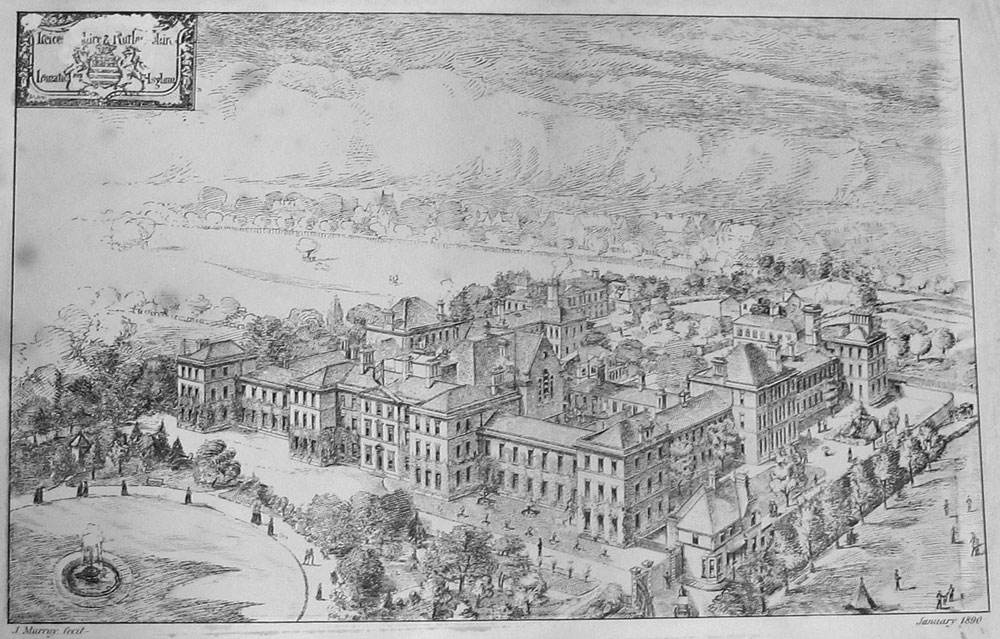

Over the past few months I have been working on listing the University of Leicester’s Administrative Archive. This work, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, is part of the “So That They May Have Life” project, carried out in order to celebrate the centenary of the University of Leicester.

My work involves exploring those early few decades of the university’s life, from its founding until after the end of the Second World War, showing the detail that goes into running a University. I have leafed through huge amounts of paper, trying to summarise what they contain so that it can be added to a catalogue which will help researchers and other potential users locate any information they might need, and help them to work out how the archive can be of most use to them. After a start heavily impacted by Covid and snow, so far this year I have added over four hundred and fifty descriptions to the listings, enabling more information to be discovered.

My previous blogs have considered the role of advertising, and how the Second World War permeated through the University, impacting on different aspects of the work that was done there. Today’s blog is going to be picking out ten highlights that I found as I was searching through the archive, now all listed which will make them easier to find.

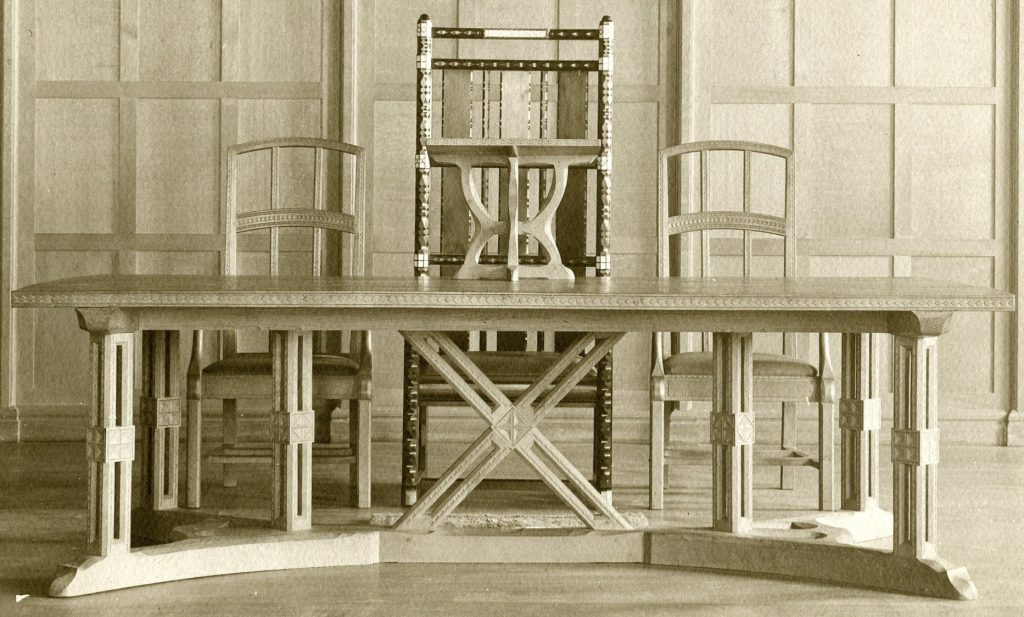

Ten – Sample of zinc. (ULA/ADM/4/1/E/ESEQ/3) Looking through orders of equipment for the college meant that I came across a huge range of information, orders for clocks and chairs, but also samples of paper, book coverings, and most surprisingly a small sample of zinc.

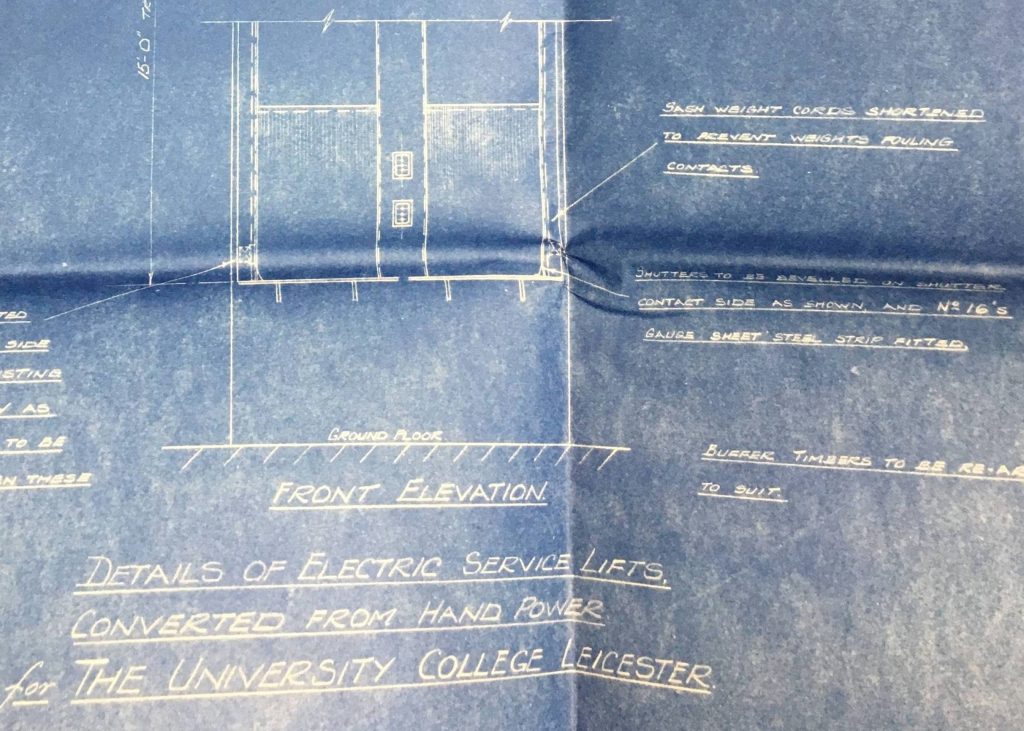

Nine – Lifts (ULA/ADM/4/1/L/LIF). Correspondence relating to service lifts included information about tenders and servicing agreements, but also blueprints, and an explanation of the necessity of a small lift to make the life of domestic staff at the hostel easier.

Eight – Stray sheep (ULA/ADM/4/1/R/RN). Among the regulations around the use of the billiard table and phone calls, there was guidance relating to stray cattle, sheep or horses found in college grounds, including details of fine rates per day for those not collected within twenty-four hours. The concept that this was a common enough problem to require regulation shows a rurality to this area of Leicester, and shows how it has changed in the past hundred years.

Seven – Student pranks (ULA/ADM/4/1/L/LAW/2). While Leicester may have changed over the past hundred years, the actions of students glimpsed in these pages feel somewhat familiar. There was a letter complaining about law school students hiding lightbulbs and throwing chalk from windows, and after a student event the “kitchen was left in a very untidy state, that students had apparently been having a fight with a pan of toast, making a shocking mess all over the floor; and that pieces of soap had been placed in the urn used for boiling water” (ULA/ADM/4/1/S/S).

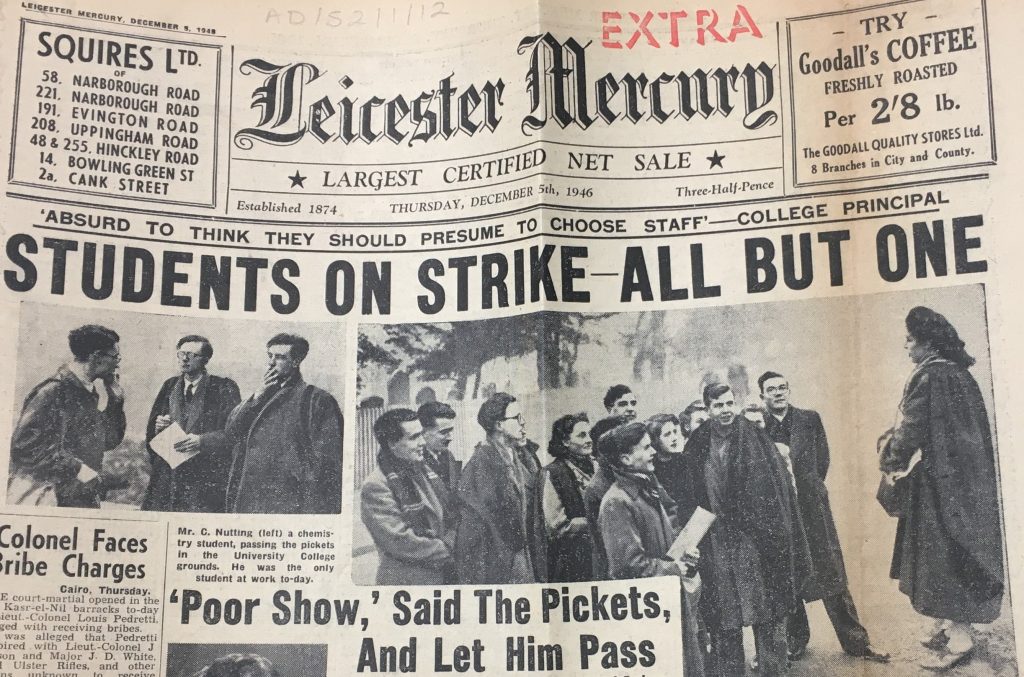

Six – Student protest (ULA/ADM/4/1/S/SU). Showing a more serious side to student life, I was interested to see the coverage of a student strike for several days following the appointment of lecturers. Cuttings from the Leicester Evening Mail and Leicester Mercury had photographs of the strikers, and information about two students who passed the picket-line.

Five – The Old Students’ Association (ULA/ADM/4/1/O/OSA/8). I was particularly delighted by an event which offered non-dancers “ample opportunities for gossip”, which is a phrase I plan to make much use of.

Four – Other Colleges. The University College early on was eager to join with Westminster training college (ULA/ADM/4/1/W/WTC), however this fell through. Later, during the Second World War, schemes were put in place for the evacuation of Hull University College ((ULA/ADM/4/1/H/HULL/1940) which were again dropped, and then finally the successful hosting of Kings’ College of Household and Social Science (ULA/ADM/4/1/K/KCHSS) for several years during the conflict.

Three – Unusual Gifts (ULA/ADM/4/1/G/GIFTS/BOOK). This book contained records of various gifts to the college, including the donor and date of the gift. Among expected books and science equipment, there were gifts of plants, a croquet set, paintings, medals, swords, glasswork, a hot plate, a printing press and the jaw bone of a sperm whale.

Two – Leicester Museum (ULA/ADM/4/1/M/MSM/3). With a strong interest in museums myself, I was fascinated by the agenda of the Museum and Art Gallery sub-committee in 1944, which included reports from various departments, including geology, entomology and archaeology. I was particularly struck by the report from the School Service department, discussing loans, children’s clubs, and visits by families and schools – all work familiar to those currently involved in the profession.

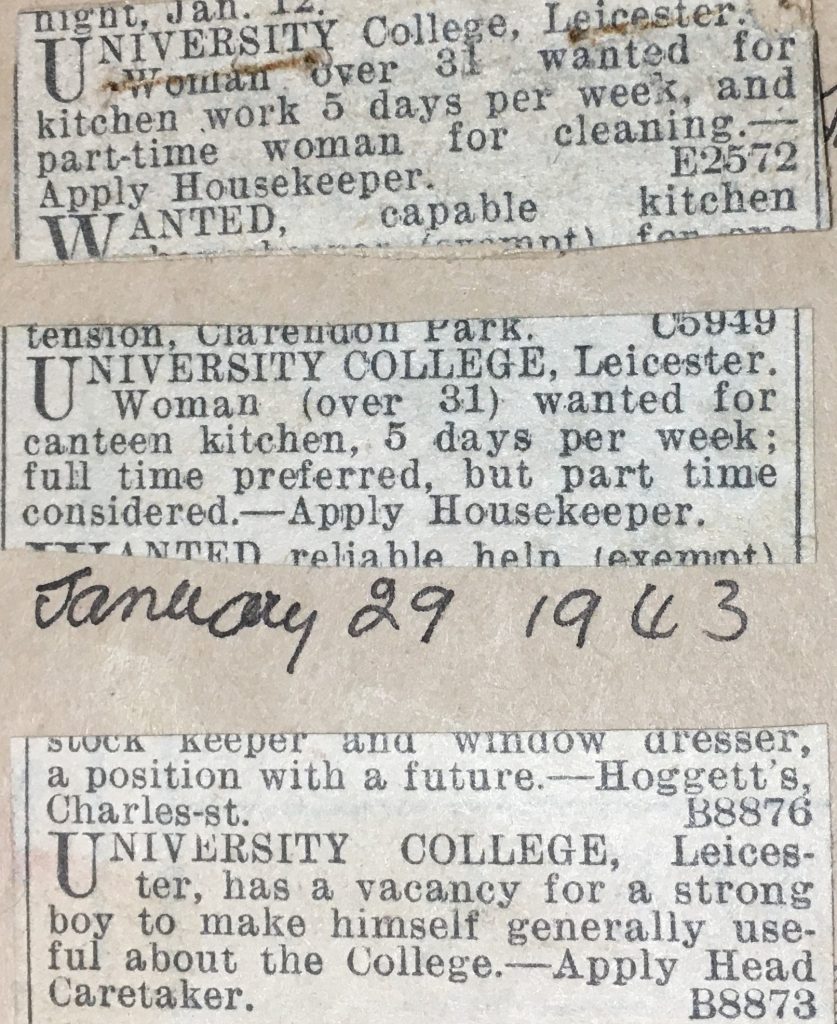

One – Lists of people. Membership lists of old students (ULA/ADM/4/1/O/OSA/4), complete with addresses, were of interest, as was information about the Industrial Ten clothing coupons which provided records of the work of various manual labourers who were entitled to extra coupons to buy overalls (ULA/ADM/4/1/S/SC). Sadly, I never found my own address among the list, but I did find a clerk during the 1930s who lived a couple of doors down from a close friend. Such lists help give an idea of the number of roles there were behind the scenes at the college, and showed the range of destinations and roles taken by students upon leaving the college. It also helps populate my image of Leicester with past lives.

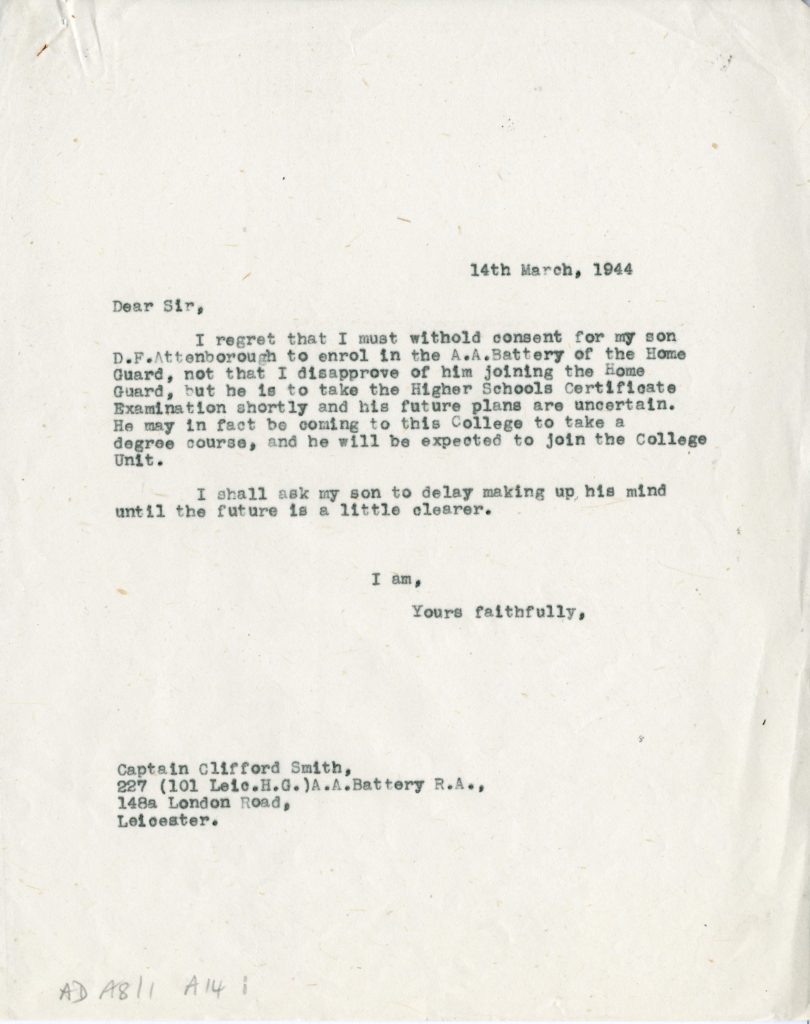

Hopefully these highlights have given you a better idea of the sheer range of objects which are contained within the University Archives, and offered a glimpse of the range of topics that are touched upon. Some of these records might feel strange, even out of place, but I feel that all of them fit in the archive together, in order to give a deeper understanding of the early life of the College. These collections expose the colourful nature of that time, and have humanised the people involved – these are real stories about real lives. That tangibility is clear in handwritten letters and typos.

Due to Covid, this role has ended up quite different from initially envisaged, with the entire country going into lockdown the night before I was due to start work. Despite this, I have received a lot of support from the archive team, and want to thank them for the support and encouragement they have given me. I am particularly thankful to Vicky Holmes, who has supported and encouraged me throughout.

I hope that reading this article has been interesting, and that if in the future you might make use of the catalogue, my work is of help. What have been your strangest archive finds?

Jenni Hunt, Temporary Archive Assistant. 26 March 2021.